The Decline of Coal : Dying Elsewhere Except in India, China

Over this decade, under relentless pressure from green activists as well as the emergence of viable alternatives, coal has been in retreat. Large sovereign wealth funds, besides Pension funds, endowments and international lenders like World Bank have undertaken their exit from financing coal power generation.

Read: IEEFA Report: China’s attachment to coal eroding Clean Energy Leadership

There are more than 100 globally significant financial institutions, with more than $10 Billion in assets under management—that have pulled out or restricted the access to financing coal industry, says Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis or IEEFA report “Over 100 Global Financial Institutions Are Exiting Coal, With More to Come”.

Highlights:

- On average, there is one new announcement every two weeks.

- The World Bank announced the first-ever restrictions in 2013, with the 100th announcement in December 2018 coming from the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) removing three country exceptions to its coal finance ban.

- Another 5 policies have been announced since the beginning of 2019 with moves coming from Nedbank of South Africa, Barclays Bank UK, Export Development Canada, and Varma of Finland.

- Latest move announced just last week was from Austria’s Vienna Insurance Group saying it will no longer insure new coal plants and mines.

Tim Buckley, Director of Energy Finance Studies, IEEFA, says when globally significant investors act, global momentum increases. He adds, “For environmental, reputational and financial reasons, thermal coal is a toxic asset for global investors increasingly announcing new and improved policies responding to climate change,” said Buckley. ” The strong leadership of a few globally significant institutions five years ago is increasingly turning into capital flight by the many, with one new announcement every two weeks in recent years.

The pace of change is electrifying

The unexpected US$18bn collapse into bankruptcy of Peabody Energy in 2016 and more recently the US$150bn collapse in value of General Electric shows the magnitude of capital destruction for investors who continue to ignore the energy system transformation. The ongoing financial distress at Wiggins Island Coal Export Terminal (WICET) in Queensland, Australia for most of this decade has bankrupted four Australian coal mining firms and cost banks and investors billions.

Since the beginning of 2018—34 coal restriction policies have been announced, with 25 being new and another nine building on earlier coal-related commitments. Notably, these restrictions are beginning to come from Asian financial institutions led by Dai-ichi Life of Japan and Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, which are rapidly aligning with their European and U.S. counterparts.

Meanwhile, some institutions in Europe and the U.S. have some catching up to do. Whilst New York City’s pension funds have pledged to divest from fossil fuels, the New York State Common Retirement Fund, the third largest pension fund in the U.S., has so far failed to act.

“The pattern of tightening existing policies combined with new lending restrictions is creating a domino effect within the global financial industry while resulting in a progressive strangulation of the thermal coal industry. Stranded assets are a clear financial risk for any institutions left funding the coal sector.” Buckley explains.

The International Energy Agency estimates that global investment in coal plants and mines has dropped by $38 billion (22%) in the past two years. While Clean energy investment, in contrast, reached $334 billion in global investment — nearly 1.5 times that of coal — in 2017.

But…

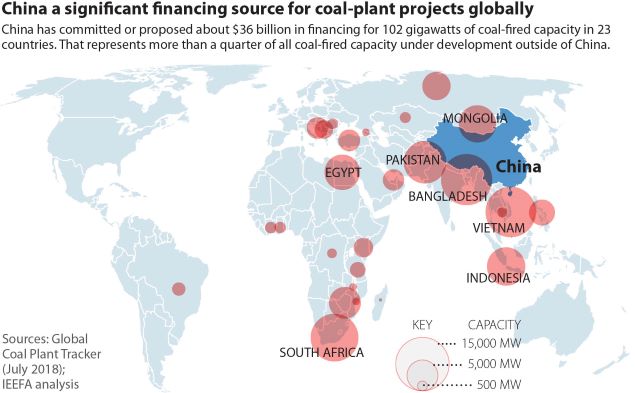

Globally, there’s still $420 billion in proposed coal plants in the pipeline, with construction finance in Southeast Asia, the last frontier for new coal expansion, coming largely from public institutions in South Korea, Japan and China. India is no exception. Some countries that have reduced coal-based generation continue to rely heavily on exports of coal (Australia) or coal-generation power equipment (China).

Read: Abandoning Coal: Japan Scraps Another Thermal Power Plant, Lessons for India

In India, State Pollution Control Boards (PCBs) have not particularly been effective at monitoring or enforcing compliance to these regulations. In the face of a competitive, regulated power market, and increasing financial pressures due to an increasingly hostile investment environment, Indian generators have few incentives to comply with regulations given their perpetual short-term liquidity problems.

Add to that the decision of Power Ministry extending the timelines to comply with emission standards for thermal plants, we can see how little momentum there is in the system for regulatory compliance.

Part of the problem is that India’s power regulators do not regularly update prices to accommodate these increases in operational costs due to regulation. The right costs by power regulators will give generators the right signals to invest in CO2 scrubbers, flue-gas desulphurisation technology (FGD), fly-ash management, and more. Otherwise, the race to the bottom on power prices will inevitably encourage power plants to skirt regulations.

Another huge issue is financing. Almost all coal power plants in India are constructed using massive debt financing from government banks, irrespective of the fact that whether the promoter is a state-owned enterprise or private firm. Odds again stack against the coal sector due to continual shocks like the cancellation of coal blocks by the Supreme Court, the bankruptcy of discoms, logistical problems leading to coal stock shortages, and a myopic coal import ban. If we look at the number of power generators which are classified as non-performing or bankrupt, this clearly shows that industry is in desperate need for capital, something India’s state-owned banks simply cannot provide at this time.

So rather than just dreaming that the problem will solve itself; multinational infrastructure investment banks can work with Indian engineering consultants and float proposals to finance CO2 scrubbers, FGD systems, and other kinds of stack emissions management in power plants.

A good example is how the city of Stockholm. The city was partially powered by an urban power plant, Vasteras, supplemented by hydropower which provided standby and peaking capacity as in when required.

This plant not only had negligible effects on air pollution in the area, but, in fact, ran cleanly for more than half a century until being slowly phased out. If we want to take a closer look at home, Torrent Power’s Sabarmati plant has been running in Ahmedabad for over 80 years and has operated well within the GPCB’s emissions norms.

We agree, Coal is on its way out in the future, but for the moment, rather than wishing it away, it should be pivoted in a direction which achieves the goals which are universally accepted at this point in time — reduce air pollution and mitigate climate change.

Picture credit: Justdial, Flickr