What stops universities from declaring a war on fossil fuels

With the science behind climate change on solid ground, the apparent reluctance of universities to throw their support behind it visibly has been dissapointing, making the efforts of students being seen now even more ironic.

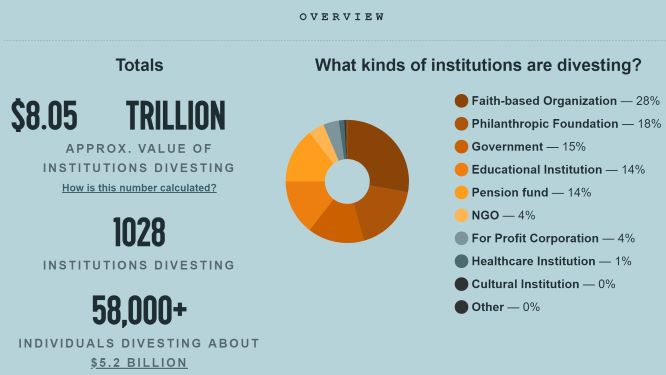

Numerous scientists and researchers have vocally or by studies informed and educated a whole generation of children, who are now adults, about the dangers of climate change and the need to move away from our addiction to fossil fuels. Finally, some institutes, too few by most counts, are coming forward to pledge to divest from fossil fuels. Most of the time it is the students, other time the government policies and rarely it is their own decision. If we take figures offered by Go fossil fuel free commitments, about 14% of educational institutions have so far come forward with their pledge to move away from the fossil fuels.

The commitments are roughly about 200 universities or campuses worldwide. Why so few? Well, we could see two reasons. First, divestment is controversial because it acknowledges the need for radical change. Second, there is a disconnect in institutional priorities between administrators on one side and faculty and students on the other side.

A Growing Global Movement

Fossil fuel divestment is intended to stigmatize the industry and hold companies accountable for opposing action to slow climate change and for deliberately obfuscating the possible impact and timelines.

To date, more than 1000 institutions with assets valued at more than $8 trillion have committed to some form of fossil fuel divestment. They include the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Guardian Media Group and the World Council of Churches.

In 2017, the UK emerged as the world leader in university divestments, with over £80 billion divested. Universities in the UK have made different sorts of pledges, with varying degrees of commitment to divest from fossil fuels. Some have also promised to invest in low carbon technologies.

There are entire cities like New York City which plans to divest its pension funds from fossil fuel companies by 2023. And in July 2018, the Irish parliament passed a bill making Ireland the first country in the world to divest from fossil fuels.

Even an oil powered economy like Norway has shifted its sovereign fund away from fossil fuels.

Increasing numbers of universities across the UK, Ireland and US are making pledges.

The University of Edinburgh — which has the largest endowment fund of any Scottish university — in 2018, committed to divest from fossil fuels, alongside a pledge to reinvest in low carbon energy sources.

The University of Glasgow has also initiated divestment from fossil fuels, which made up a significant (14 percent) portion of their endowment. The University of Glasgow was also the first in the UK – and indeed the whole of Europe – to announce it’s divestment from fossil fuels in 2014, followed by several others throughout 2015-18, including the University of Oxford, Edinburg, SOAS, and London School of Economics.

Around two-thirds of the ‘elite’ Russell Group universities have so far divested. These universities are the among the oldest in the UK, and generally, have the largest investment funds.

What stops the Campuses?

Faculty support reflects concern about fossil fuel companies’ negative influence in an increasingly unequal economy and in public understanding of science. Faculty are also concerned about the industry’s direct influence over research and teaching within higher education. We see a classic example of conflict of Interest.

A wide array of prestigious schools, ranging from large state universities to prestigious elite institutions such as Harvard and MIT or in India IITs and IIMs, receive financial support from individuals or foundations whose wealth comes from fossil fuels. Like in US–MIT’s Energy Initiative is almost entirely funded by fossil fuel companies, including Shell, ExxonMobil, and Chevron. MIT has taken $185 million from oil billionaire and climate denial financier David Koch. Stanford university’s Global Climate and Energy Project is funded by ExxonMobil and Schlumberger. Many professors and students are concerned about how these relationships constrain campus research, inquiry and conversation about responses to climate change and the need for radical change in energy systems.

The other Russell Group universities (UK) that have not divested —are Birmingham, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Mottingham, Exeter and York, and Imperial College London.

Earlier institutions like Harvard, Swarthmore, Middlebury resisted faculty and student calls to divest. Recently the University of Guelph rejected the call for divestment. Many administrators cite their fiduciary responsibility to maximize returns on endowment investments.

Many schools are now implicitly acknowledging this by developing guidelines for socially or environmentally responsible investing.

Senior administrators may also fear alienating important university alumni who are connected to the fossil fuel industry. They may feel a need to protect direct or indirect funding from fossil fuel companies for academic programs, or to maintain a non-threatening environment for board members with fossil fuel interests.

A Way Forward

The core missions of our institutions of higher education are to generate knowledge and educate citizens and leaders. Many schools also embrace a third role: addressing pressing social issues, whether through research and teaching or other strategies. It is here that they need to relook if they have been amiss.

Education scholars have argued that all universities transmit powerful educational messages far beyond their specific teaching and research activities. Concepts of “universities as citizens” or “universities as change agents” capture the potential for universities to be active, contributing, influential and responsive members of society.

Picture credit: Flickr, 350.org