Wetlands to the rescue in Kolkata.

By Sahana Ghosh

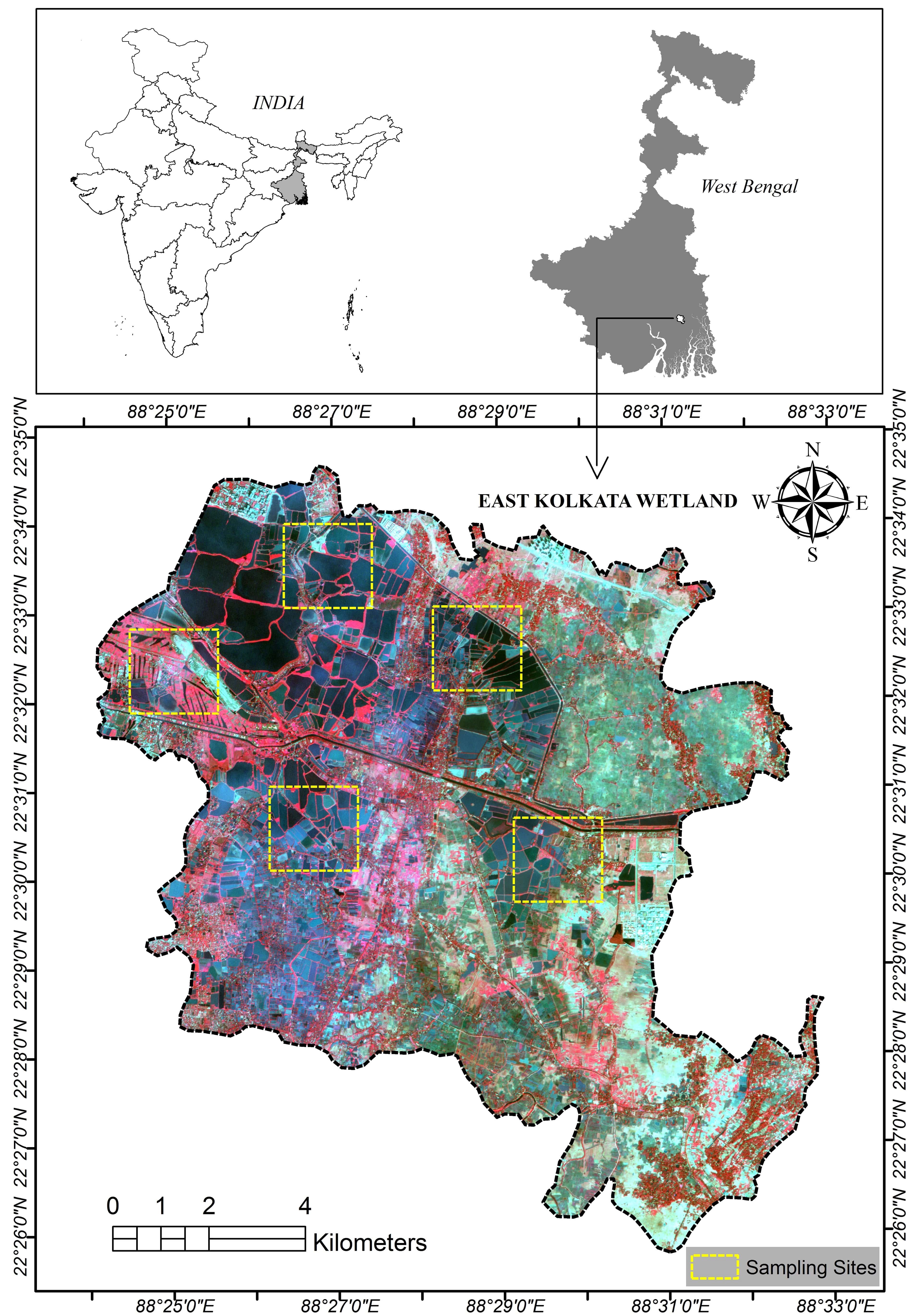

- The East Kolkata Wetlands with an area of 125 square km enjoys the unique distinction of being the largest ‘wastewater-fed aquaculture system’ in the world where the sewage is recycled for pisciculture and agriculture.

- The wetlands act as a carbon sink and clean up the city’s air. Kolkata’s core area does not have a sewage treatment plant.

- This long-term lockdown of excess carbon needs to be recognised and recorded in view of encroachment threats to the EKW as well as against the backdrop of India’s plan to create additional carbon sinks in line with the landmark Paris Accord.

Architecturally discordant high-rises and garish billboards screaming their products mask a placid blue-green expanse to the east of the Indian metropolis of Kolkata. Rushing through a busy day, commuters are barely aware of the East Kolkata Wetlands, which for over a century has been quietly flushing filth out of the city’s system and cleaning its air.

Wetlands cover approximately four to six percent of the Earth’s surface and contain about 35 percent of global terrestrial carbon. In India, wetlands cover an estimated three percent of India’s land area.

Groaning under the weight of encroachments, the rapidly shrinking East Kolkata Wetlands (EKW), is considered the largest natural treatment system for solid and soluble waste and is a Ramsar site (Wetlands of International Importance).

Additionally, EKW claims the unique distinction of being the largest ‘wastewater-fed aquaculture system’ in the world where the sewage is recycled for pisciculture and agriculture. The megacity’s core area does not have a sewage treatment plant.

Now, researchers have shown that the internationally recognised EKW locks-in over 60 percent of carbon from the wastewater it encounters, which might otherwise pile up in the atmosphere.

“The wetlands act as a carbon sink and clean up the city’s air. The carbon is sequestered in soil and biota (plant and animal life) of the EKW ecosystem. If this 60 percent carbon is not stored by the EKW then it would have dissipated into the atmosphere,” says study author Sudin Pal, of the Department of Chemical Engineering, Jadavpur University, Kolkata.

Crisscrossed by creeks and canals, a mosaic of nearly 254 sewage-fed fishponds (bheris), agricultural land, garbage-farming areas and settlements make up the 125-square-km (12,500 hectare) wetlands that form an important portion of the mature delta of Ganga River.

In the wake of urbanisation and vocation change observed among the EKW’s farming and fishing community, Pal and colleagues sought to flesh out the carbon storing efficiency of the waterbody and map its role in mitigating global warming and accumulation of greenhouse gas emissions.

This long-term lockdown of excess carbon needs to be recognised and recorded in view of encroachment threats to the EKW as well as against the backdrop of India’splan to create additional carbon sinks in line with the landmark Paris accord, argue researchers.

The researchers crunched data on organic and inorganic carbon content of wastewater and wastewater-fed fishponds across seven sampling sites along a 40-km stretch of the wetlands.

“The study sites include some of the most polluted stretches of the city such as tannery conglomerates linked to China Town, a tannery effluent-fed fish pond, a composite wastewater-fed fish pond and a site where tannery effluent was mixed with municipal wastewater and other small-scale industrial effluents,” Pal told Mongabay-India.

An ‘ecological subsidy’ for Kolkata

The wetlands save Kolkata, India’s seventh most populous city, a staggering Rs. 4,680 million a year in sewage treatment costs.

About 1,000 million litres of wastewater each day is funneled into the wetlands that filter it and discharge it in the Bay of Bengal some three or four weeks later.

It takes care of more than 80 percent of the metropolis’s sewage, supports around 50,000 agro-workers and supplies about one-third of Kolkata’s requirement of fish, says Pal.

“Kolkata has remained an ‘ecologically subsidised city’ since the British Raj as the government doesn’t need to invest in wastewater treatment for the city,” he says.

But he points out that over four decades (between 1972 and 2011), about 38.6 square km of wetlands were converted to built-up areas.

“The importance of wetlands in rendering ecosystem services and solving the water crisis are recognised globally. Only motivated conservation efforts can resist further shrinkage of this sustainably productive natural treatment system in Kolkata’s backyard,” Pal adds.

Vocation switch

The disruption of the critical ecological balance in the wetlands that impacts fishing and farming activities, is linked to the community giving up these activities, declares urban economist Mahalaya Chatterjee.

“The ecological balance is disturbed due to various factors such as obstruction of wastewater flow due to encroachment and other reasons, siltation in bheris and the changing signature of bio-chemical components in sewage water,” says Chatterjee of the University of Calcutta.

In addition, with scope for better education and lure of modern employment opportunities, fishing and farming have started losing appeal among the young generation.

To tackle this switch, Pal and colleagues have proposed a carbon credit system for the farmers who have organically and unknowingly contributed to the ecosystem services by growing produce that sequesters carbon.

Besides the sewage-driven pisciculture, other connected activities in the area that also trap carbon include paddy cultivation, farming of vegetables, poultry and animal husbandry.

Pal reasons, farmers can boost the carbon sequestration potential of their farms and other sites and gain economic incentive through a system of carbon credits.

“Given the fact that the next generation does not want to adhere to the same vocation, a carbon credit system would help retain them in the vocation of farming which is essential to the survival of the wetlands,” he explains.

Waste into wealth

The wetlands transform the untreated, nutrient-rich raw tannery effluent, municipal and industrial wastewater they receive, into 18,000 tons fish yields per year and nearly 150 tons of vegetable produce daily, says Pal.

Aquaculture and sewage treatment work complementarily, like the cogs of a well-oiled machine.

When the sewage arrives in the series of interconnected ‘bheris’ (shallow fish ponds), it is allowed to stand in the sun, letting bacteria and algae work their magic on the sewage and convert the waste into forms useful for fish feeds, says economist Debanjana Dey. The synergistic growth of bacteria and algae, in turn, is boosted by the nutrients in the waste water.

Commending the mastery of the fishermen over the resource recovery activity, Dey points out the yield of fish from the bheris is two to four-fold more than the volume achievable through normal ponds.

“They know exactly how to excavate the ponds to the correct depth, clean the water by spraying kerosene, lime and oil cakes (khol), mix the right quantity of sewage, allow optimal time for conversion of the waste into fish feed, when to add spawns, how to protect the embankments through water hyacinths and so on,” say Dey and co-author Sarmila Banerjee in a chapter of the book ‘Sustainable Urbanisation in India’.

The biggest sources of carbon in the EKW area are the solid and liquid wastes from the tannery industries with tannery waste typically containing a complex mixture of both organic and inorganic pollutants, informs Pal.

The municipal sewage water was also a significant source of TOC (total organic carbon) in EKW. The inorganic carbon (total inorganic carbon or TIC) mainly came from the tannery sludge.

“This decrease in carbon in wastewater was possible because of the flow-rate of wastewater in the carrying canals, long residence time in the wastewater-fed fish ponds and repeated use of wastewater in irrigating agricultural fields at the EKW ecosystem. However, the wetlands need to be managed properly to curb methane emissions,” Pal concludes.

To read the full article, which appeared on Mongabay.com, pls visit this link